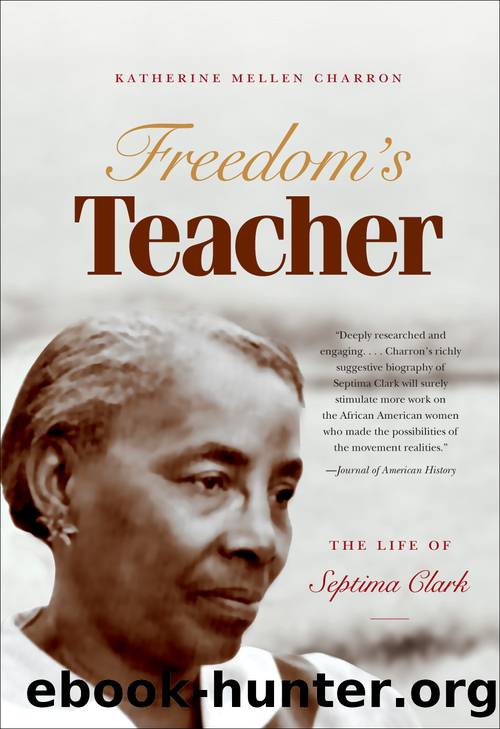

Freedom's Teacher by Katherine Mellen Charron

Author:Katherine Mellen Charron

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2009-01-15T00:00:00+00:00

The African American children at Septima Clarkâs school, Archer Elementary, had offered some spirited responses to Brown. âTheyâll be plenty of fighting now,â one boy predicted, while another chimed, âThe first one to call me a nigger, Iâll bop him in the nose.â Many complained, âI donât want to go to school with them.â The forward-looking expected to enter white high schools but dared their future classmates âto say anything to me.â One third-grader advised his teacher âthat he was leaving the next day because he lived near a white school.â White students had their own reactions as well. As Clarkâs principal left one afternoon, he overheard a group of white boys snarl, âThatâs the nigger who is going to be over us.â46 Maybe they repeated what they had heard at home. What their parents said and did was infinitely more frightening.

In the months and years that followed the Supreme Courtâs 1954 decision and its implementation decree issued a year later, white people across the South went on the offensive to protect their segregated way of life. Robert Patterson organized the first chapter of the all-white Citizensâ Council (CC) on July 11, 1954, in the Mississippi Delta. White South Carolinians established their inaugural branch in Elloree the same month that Highlander hosted its United Nations workshop in August 1955. Less than six months later, South Carolina counted a total of fifty-six CC chapters and significant backing from the stateâs political leaders. U.S. representative L. Mendel Rivers, from Charlestonâs First District, identified himself as a member. U.S. senators Strom Thurmond and Olin D. Johnston thought it best not to join but publicly affirmed their support for the organization.47

Solidifying public opinion behind the preservation of segregation and organizing local resistance to federal intrusion formed the backbone of the CCâs agenda. It drew members from the upper and middle classes, respectable civic leaders and businessmen who literally had considerable investments in preserving white economic and political power. Participation by their wives ensured the success of the covered dish suppers and Low Country oyster roasts that served as a pretext for more serious business and validated assertions that the âCouncil movement is truly a peopleâs movement . . . organized from the bottom to the top, rather than the top to the bottom.â The editor of the Charleston News and Courier, Thomas R. Waring Jr., described CC members as âamong the best peopleâ in South Carolina, âthe citizens who belong to the civic clubs and the churches . . . and do the other housekeeping chores of a community.â Joe Brown, president of the Charleston NAACP branch, dubbed them âthe tuxedo gang of the Ku Klux Klan.â Unlike the Klan, CC leaders publicly disavowed violence, preferring to rely instead on economic intimidation and legislative action.48

Staying within the law was hardly difficult for the men who wrote it, and white Carolinian legislators had been preparing specifically for the Brown decision for a good three years before it was handed down on May 17, 1954. In

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(9109)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi(8408)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7870)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7789)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6924)

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(5241)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4943)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4911)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(4753)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4722)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4565)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4448)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(4338)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4295)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4174)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(4116)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(4110)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3966)